A Beginners Guide to Fuel Hedging with Futures

As companies begin to plan for the second half of the year, we’ve been fielding numerous inquiries from companies who are interested in developing a fuel hedging program for the first time in their company’s history. If you lack the knowledge to consider yourself a fuel hedging expert, this post along with several more that we'll be publishing shortly, will help you obtain a better understanding of most common fuel hedging strategies available to commercial and industrial fuel consumers.

For starters, what is a futures contract? A futures contract is simply a standardized contract, between two parties to buy or sell a specific quantity and quality of a commodity for a price agreed upon at the time the transaction takes place, with delivery and payment occurring at a specified future date. The contracts are generally traded on a futures exchange, such as ICE or CME Group’s NYMEX, which acts as an intermediary between the buyer and seller and are often facilitated by a futures clearing firm (FCM) or introducing broker (IB). The party agreeing to buy the futures contract, the "buyer", is said to be "long" the futures while the party agreeing to sell the futures contract, the "seller" of the contract, is said to be "short" the futures.

In essence, a futures contract obliges the buyer of the contract to buy the underlying commodity at the price at which he bought the futures contract. Similarly, a futures contract also obliges the seller of the contract to sell the underlying commodity at the price at which he sold the futures contract. In practice, very few futures contracts result in delivery, as most are utilized for hedging and speculation are bought back or sold back prior to expiration.

There are three primary futures contracts which are commonly used for fuel hedging: ULSD (ultra-low sulfur diesel) and RBOB gasoline, which are traded on CME Group’s NYMEX and gasoil, which is traded on ICE. Regardless of whether you're looking at hedging bunker fuel, diesel fuel, gasoline, jet fuel or any other refined product, these three contracts serve as the primary benchmarks for refined products across the world.

In addition, there are many other contracts (futures, swaps and options) available for fuel hedging, most of which are tied to one of the major, global trading hubs of Singapore, US Gulf Coast (Houston/New Orleans), NW Europe/ARA (Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Antwerp) and the Arab Gulf. As an aside, the CME/NYMEX futures contract was previously known as heating oil and as such still trades under the symbol HO. For more information on the transition from heating oil to ULSD see NYMEX Heating Oil Completes Transition to Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel.

Diesel Fuel (ULSD) Hedging Example

So how can you utilize a futures contract to hedge your exposure to rising fuel prices? Let's assume that your company owns or leases a large fleet of vehicles and, to ensure that your fuel costs do not exceed your budgeted fuel price, you have been asked to "fix" or "lock in" the price of your anticipated fuel consumption. For sake of simplicity, let's assume that you are located in the Americas and are looking to hedge (by "fixing" or "locking" in the price) 42,000 gallons of ULSD (diesel fuel) which you anticipate consuming in August.

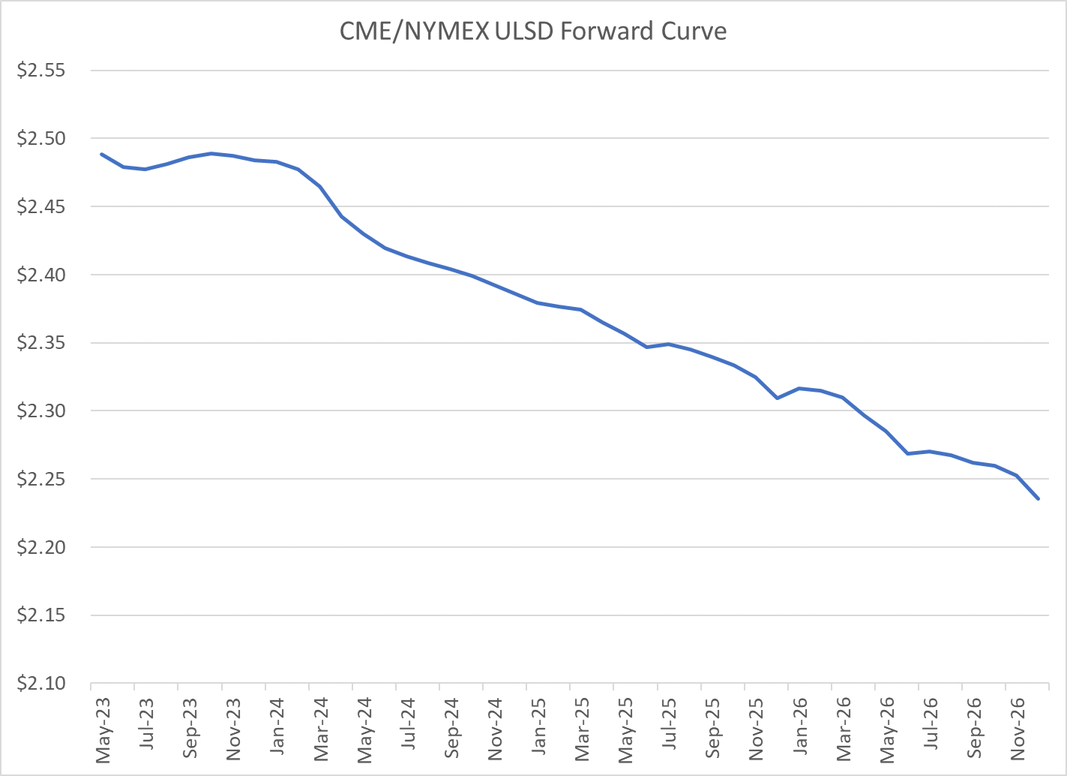

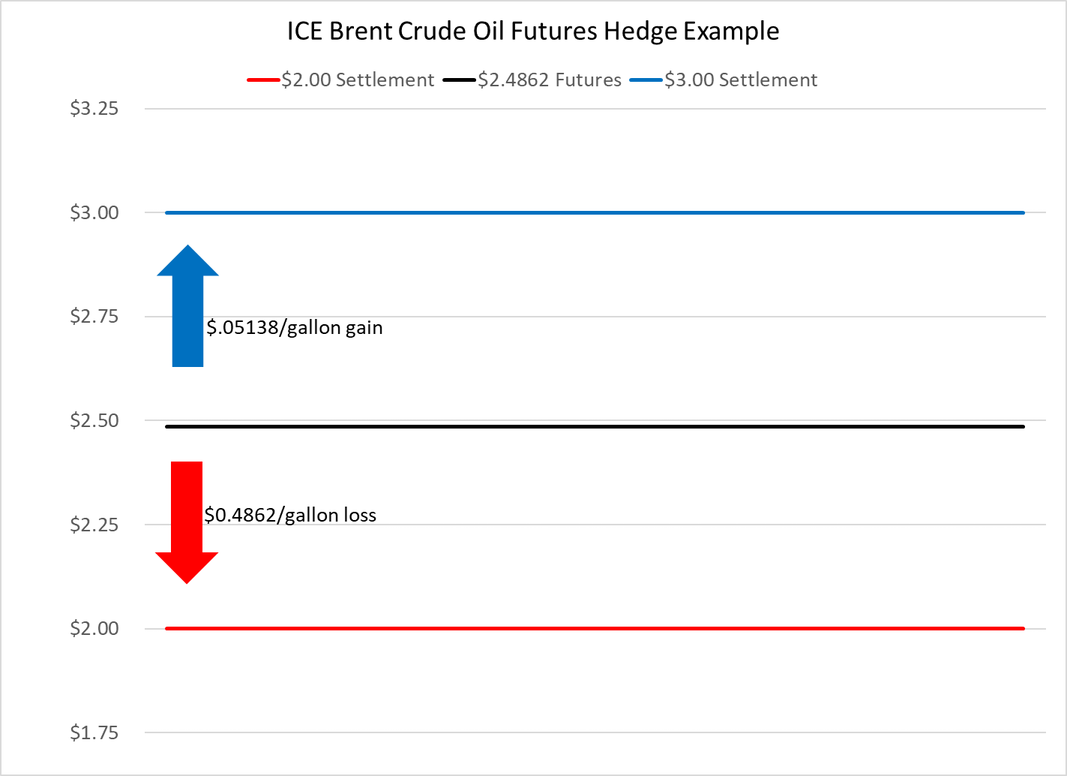

To accomplish this, you could purchase one NYMEX September ULSD futures contract, which happens to trade in 42,000-gallon (42,000 gallons = 1,000 barrels) increments. If you had purchased this contract based on the closing price yesterday, you could have hedged your August diesel fuel for $2.4862/gallon (which excludes taxes and basis differentials as well as distribution and transportation fees).

Now let’s theoretically fast forward to August 31, the expiration date of the September ULSD futures contract. Because you do not want to take delivery of 42,000 gallons of ULSD in New York Harbor, the delivery point of the NYMEX ULSD futures contract, you decide to close out your position by "selling back" one September ULSD futures contract at the then, prevailing market price.

In scenario one, let's assume that the prevailing market price, at which you sold back the futures, was $3.00/gallon. In this scenario, your gain on the futures contract would equate to a profit of $0.5138/gallon ($3.00-$2.4862=$0.5138). As such, in this scenario your net cost will be the price you pay “at the pump” minus your hedging gain of $0.5138/gallon, thanks to your hedging gain.

In scenario two, let's assume that the prevailing market price, at which you sold back the futures, was $2.00/gallon. In this scenario you would incur a loss, rather than a gain as in the first example, on the futures contract of $0.4862/gallon ($2.4862-$2.00=$0.4862). Contrary to the first scenario, in this scenario your net cost will be the price you pay “at the pump” minus your hedging loss of $0.4862/gallon, due to your hedging gain.

As this example indicates, purchasing a ULSD futures contract provides you with the ability to hedge or fix your anticipated diesel fuel costs for a specific month(s), regardless of whether the price of ULSD futures increase or decreases between the date that you purchased the futures contract and the date the futures contract expires.

While this example focused on hedging diesel fuel with ULSD futures, the same methodology applies to hedging gasoil, gasoline, heating oil, jet fuel, etc.

While there are many details that need to be considered before hedging with futures, the basic methodology of hedging fuel price risk with futures is simple. That is, if you need to hedge your exposure to potentially rising fuel prices you can do so by purchasing a futures contract. On the other hand, if you need to hedge your exposure to declining fuel prices, you can do so by selling a futures contract.

Caveat emptor - Most companies will find that hedging their fuel price exposure is less than ideal as futures contracts expire on a specific day of the month and most businesses consume fuel every day. As such, many companies find that swaps - or alternative futures contracts which act as “look-a-likes” to swaps (e.g. the NYMEX NY Harbor ULSD Financial futures) serve as a better hedging tool than the primary futures contracts as most fuel swaps generally settle against the monthly average price (more on this in an upcoming post) which is more consistent with how commercial and industrial fuel consumers purchase fuel.

This post is the first in the series on fuel hedging for commercial and industrial consumers such as corporate fleets. The subsequent posts in the series can be found via the following links: