Energy Hedging 101 - Options

This post is the third of several in a series covering the basics of energy hedging. Here are the links to the first and second posts, which covered energy hedging with futures and energy hedging with swaps.

In subsequent posts in this series, we will also be exploring the basics of more "complex" hedging structures such as basis swaps, collars and option spreads.

An option is contract which provides the buyer of the contract the right, but not the obligation, to purchase or sell a particular amount of a specific commodity on or before a specific date or period of time.

There are two primary types of options, call options (also known as a caps) and put options (also knows as floors). A call option provides the buyer of a call option with protection against rising prices. Conversely, a put option provides the buyer of the put option with protection against declining prices.

Energy consumers often utilize call options to mitigate their exposure to rising energy prices, including but not limited to electricity, diesel fuel, gasoline, heating oil, propane, etc.

Energy producers often utilize put options to mitigate their exposure to declining energy prices, such as crude oil, natural gas and natural gas liquids.

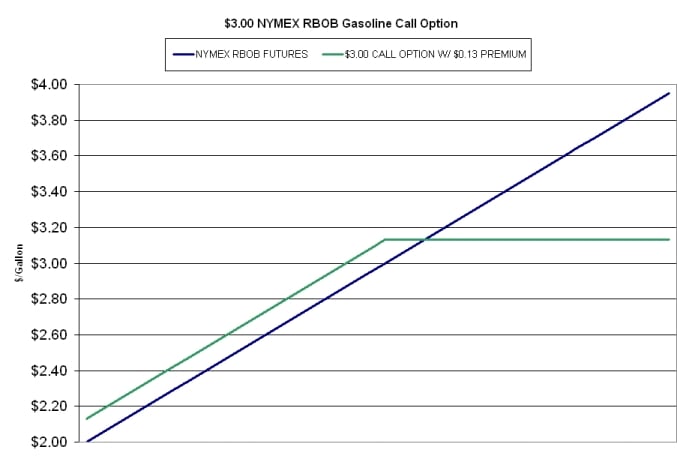

As an example of how an end-user (consumer) utilize a call option, let's assume that you're company has a large fleet and in order to ensure that your gasoline expenses do not exceed your budget, you need to cap the price of your anticipated cost of your gasoline consumption for a specific month. For sake of simplicity, let's assume that you are looking to hedge 100% of your anticipated, May 2011 gasoline consumption, which equates to 125,000 gallons.

In order to do accomplish this you could purchase a May 2011, NYMEX RBOB gasoline, average price call option from an energy trading company. Furthermore, let's assume that you wanted to mitigate your exposure above $3.00 per gallon (excluding basis and taxes). If you had purchased this option last Friday, it would have cost you approximately 13 cents per gallon or $16,250 ($0.1300 X 125,000 gallons).

Now let's examine how this option would perform if gasoline prices both increase and decrease between now and the end of May.

In the first scenario, let's assume that fuel prices increase and that the average price for NYMEX RBOB gasoline futures for each business day in May, was $3.50/gallon. In this scenario, your hedge would result in a "gain" of 50 cents per gallon ($3.50 – $3.0000 = $0.50) or $62,500. As a result, you would receive a payment of $62,500 from the energy trading company, which would offset the increase in your actual fuel expenses by $0.50/gallon. However, given that you paid 13 cents per gallon, your net gain would be 37 cents per gallon or $46,250.

In the second scenario, let's assume that fuel prices decrease and that the average price for NYMEX RBOB gasoline futures for each business day in May, was $2.75/gallon. In this scenario, your hedge would be "out-of-the-money" and you would not receive a return on the option. However, given that gasoline futures prices have decreased, so should your actual gasoline costs at the pump. Last but not least, given that you paid 13 cents for the option, your actual net cost per gallon would need to account for the 13 cent premium cost.

As this example shows, purchasing a gasoline call option allows companies which consumes large quantities of gasoline to hedge their exposure against rising gasoline prices.

The following chart shows the "payoff" of the $3.00 gasoline call option described above. As you can see, when gasoline futures are below $3.00 per gallon, the company's net price is equal to the gasoline futures plus 13 cents (the price of the option). Conversely, when the futures are above 13 cents per gallon, the company's net price remains $3.13 ($3.00 + $0.13).

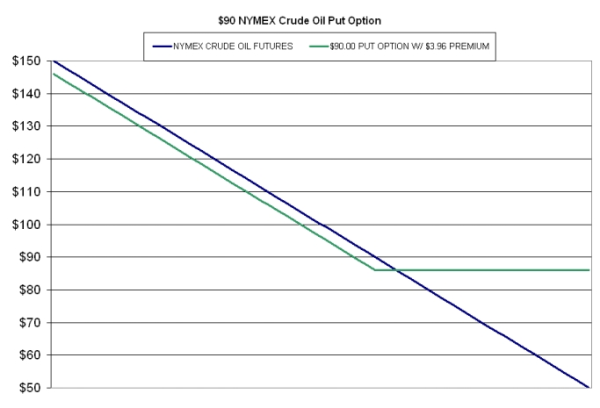

As an example of how an producer utilize a put option, let's assume that you're an Oklahoma oil and gas producer who needs to hedge your exposure to potentially declining crude oil prices in a specific month. For sake of simplicity, let's assume that you are looking to hedge 100% of your anticipated, September 2011 crude oil production, which estimated to be 10,000 barrels.

In order to do accomplish this you could purchase a September 2011, NYMEX WTI crude oil, average price put option from your bank's commodity trading desk. Furthermore, let's assume that you wanted to mitigate your exposure below $90 per barrel. If you had purchased the September 2011 $90 put option last Friday, it would have cost you approximately $3.96 per barrel or $39,600 ($3.96 X 10,000 barrels).

Now let's examine how this option would perform if crude oil prices both increase and decrease between now and the end of May.

In the first scenario, let's assume that crude oil prices decrease and that the average price for NYMEX crude oil futures for each business day in September, was $75.00/barrel. In this scenario, your hedge would result in a "gain" of 15 dollars per barrel ($90 – $75 = $15) or $150,000 (10,000 barrels X $15/barrel). As a result, you would receive a payment of $150,000 from your bank, which would offset the decrease in the price you receive, at the wellhead, from your production. However, given that you paid $3.96 per barrel for the option, your net gain would be $11.04 per barrel ($15.00 - $3.96) or $110,400.

In the second scenario, let's assume that crude oil prices increase and that the average price for NYMEX crude oil futures for each business day in September, was $125 per barrel. In this scenario, your hedge would be "out-of-the-money" and you would not receive a return on the option. However, given that crude oil futures prices have increased, the actual price that you realize at the wellhead should also have increased accordingly. However, recall that you paid $3.96/barrel for the option, so your actual net revenue per barrel including the cost of the option would be $121.01/barrel (assuming your marketer paid you $125 per barrel).

The following chart shows the "payoff" of the $90.00 crude oil put option described above. As you can see, when crude futures are below $90.00 per barrel, the oil producer's net price is equal to $86.04.barrel ($90 - $3.96). Conversely, when the futures are above $90 per barrel, the oil producer's net price is the NYMEX crude oil futures minus $3.96/barrel.

As this example shows, purchasing a put option allows companies such as oil and gas producers to hedge their exposure against declining crude oil prices.

While this example showed how put options can be used to hedge crude oil price risk, the same methodology can also be used to hedge natural gas, natural gas liquids (NGLs), etc.

Next week when we'll be discussing a few of the "more complex" energy hedging strategies and instruments.

UPDATE: This post is the third post in a series of five on the basics of energy hedging. The previous and subsequent posts can be found via the following links:

Energy Hedging 101 - Basis Swaps

In the meantime, if you would like to learn more about hedging your exposure to volatile energy prices with options please feel free to contact us.