Crude Oil Hedging in An Uncertain Environment - $30 or $200

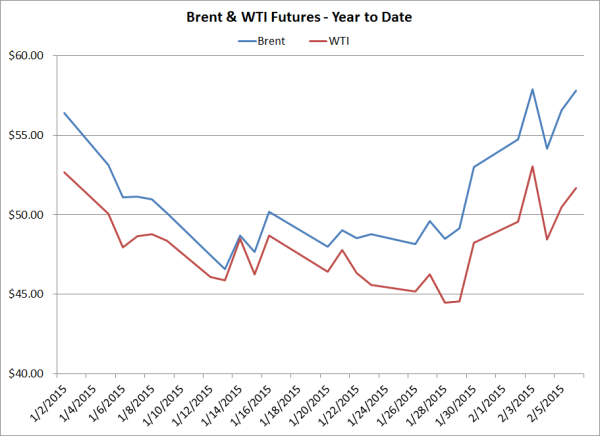

WTI has traded in a volatile range lately, as have Brent and all other grades of crude oil. The prompt WTI crude oil contract lost more than 8% of its value (Feb 3 close = $53.05, Feb 4 close = 48.45, change = -$4.60/bbl) on a single day last week. Such volatility is great for news agencies that write stories about extreme price movements, often accompanied by sensational quotes from market participants. For example, CNN Money used a quote from OPEC Secretary General Abdulla al-Badri to write the headline: “OPEC leader: Oil could shoot back to $200.” To paraphrase, Mr. al-Badri does not believe oil prices will fall any lower. He cites falling CapEx and rig counts, going so far as to say there is risk that oil producers may over react, resulting in under investment in oil supply, subsequently resulting in a tighter, maybe under-supplied, oil market. He uses $200 as the result of an extreme case of lost investment combined with the natural decline of existing production. As an aside, a recent Bloomberg article summed up the current market uncertainty quite well - These Experts Know Exactly Where Oil Prices Are Headed - Somewhere Between $30 and $200 a Barrel

This is actually a very important point; a rare gem found in online media that usually focuses on daily price change and geopolitical headlines. Al-Badri is right, at least theoretically. $200 may be the wrong number, but there is definitely an inverse correlation between supply and price. As investment in supply falls, supply may eventually fall (adjusted for efficiency improvements, cost reduction, etc.). But what does that mean for your risk management program? Risk managers have to monitor a wide variety of factors to understand the risk inherent in their business. This is important to all market participants, no matter where they lie on the value chain from producers down to consumers. This post examines volatility and fundamentals as inputs to risk management decisions.

Volatility is an often-misused input. It is often a substitute for risk, largely because you can quantify volatility in a way that gives managers a dollar figure exposure, i.e. – value at risk, better known as VaR. For many risk managers who specifically focus on how prices affect the core business of their company, this is an incomplete story to say the least. Volatility isn’t itself a risk, per se. If prices rise from $49.45 at the close of business (settlement) today and rise to $149.45 by noon tomorrow, but eventually settle tomorrow at $49.45, volatility had no effect on your bottom line (assuming that you weren’t subject to an unmanageable intraday margin call). On the other hand, if prices gradually rise from $49.45 to $149.45 over the next few months or years, without ever falling back to $49.45, consumers are much worse off. Clearly, the opposite is true for producers.

In both highly volatile markets and those with zero volatility, intelligent, conservative companies will have a plan of action related to their hedging needs. In other words, a consumer whose costs are highly sensitive to oil prices will want to hedge against the potential rise, regardless of market condition. This is especially true for companies with little or no control over the price at which they sell their product. This is why we encourage our clients to utilize volatility as an input to hedging decisions and an input for analysis of exposure, not just a single-number exposure measurement itself. For example, a consumer may use volatility as an input in his process of choosing from a menu of potential hedging strategies. If prices have moved drastically higher recently, his policy might encourage him to hedge by purchasing a call options or a call spread. Alternatively, if prices have demonstrated little volatility, his policy might advise him to consider hedging with fixed price swaps. It depends on the specific scenario, your specific business, and perhaps most importantly, your risk tolerance. The key to success in such an uncertain market environment – have a clearly defined policy with decision-making guidelines. Producers and consumers should regularly review their policy and strategy, but volatility isn’t an excuse to abandon the policy or strategy without analysis, no matter how much stress it may cause.

Likewise, risk managers should use fundamentals as inputs in your analysis. Of course, fundamentals have a tendency to be long term, in contrast to volatility’s shorter-term focus. Comments like those from OPEC Secretary General Abdulla al-Badri do not qualify as fundamental analysis. If you choose to perform fundamental analysis, you need to adapt it to your specific business. Secretary al-Badri was speaking in generalities, but was speaking about fundamentals. Your analysis won’t be rooted in his comments, or any media source, for that matter. However, it might be worthwhile to build a fundamental analysis model rooted in the variables most important to your business. If you are a buyer of crude oil, you may want to understand how global and regional upstream CapEx (capital expenditures) might affect supply in the long term. This will help you understand developing long-term trends and might be useful for making investment decisions. Hedging cannot change the fundamentals of the market. Rather, hedging is temporary protection from adverse price movements, which tend to exaggerate the fundamental picture in the near term. Recent price movements are no exception. It’s possible that the price of oil has fallen below the fundamental equilibrium price. You have no way of knowing that equilibrium, so it is important that you have done the analysis necessary to understand the impact of changing prices on your business and how you can incorporate said analysis into your decision making process.

Ultimately, a well-designed energy hedging program will mitigate the risk associated with volatility and while utilizing fundamentals, as well as other relevant analysis and risk metrics, to give you a solid foundation by which you can make sound business decisions. Your hedging program should also include well thought out analysis of fundamentals and volatility that clearly articulate your specific exposures in terms that are important to your core business. This analysis often takes up more time than the execution of trading, as it should. Better to measure twice and cut once.