An Introduction to Energy Basis, Basis Risk and Basis Hedging

Nearly every day our team spends a meaningful amount of time discussing basis differentials, basis risk and mitigating basis risk, yet basis is a topic that is far too often neglected – both knowingly and unknowingly – by many market participants.

Energy basis – what is it and how can it be hedged?

What is basis? In simple terms, it's the difference between the price of an energy commodity in one market and the price of the same or similar energy commodity in a different market. The different “market” can be a different location, also known as locational or geographical basis (e.g., US Gulf Coast ultra-low sulfur diesel vs. New York Harbor ultra-low sulfur diesel), a different product or quality which we can be referred to as product or quality basis (e.g. Singapore gasoil vs. Singapore jet fuel) or a different tenor, duration or time frame (e.g. a November NYMEX WTI crude oil future vs. a December NYMEX WTI crude oil future), which we refer to as "calendar basis". Why is understanding basis, and basis risk, a key factor in energy price risk management? Let's explore a few examples.

Locational basis risk is the risk that you encounter when you hedge with a contract that doesn't have the same or similar delivery point as the risk you are seeking to hedge. As an example, if a US Gulf Coast oil producer decides to hedge their crude oil price risk with NYMEX WTI futures (which are deliverable in Cushing, Oklahoma), the producer is exposed to the locational basis risk between Cushing and their local market price in the Gulf Coast e.g., WTI Houston. To quantify this example, the December WTI Cushing crude oil swap closed yesterday at $72.48/BBL, while the December WTI Houston crude oil basis swap closed yesterday at $1.30/BBL. This indicates that the forward market for December WTI Houston is trading at a $1.30 premium to December WTI Cushing. In a future post we will explore how a Gulf Coast producer, and other market participants, can mitigate their exposure to locational basis risk by hedging with basis swaps and other strategies.

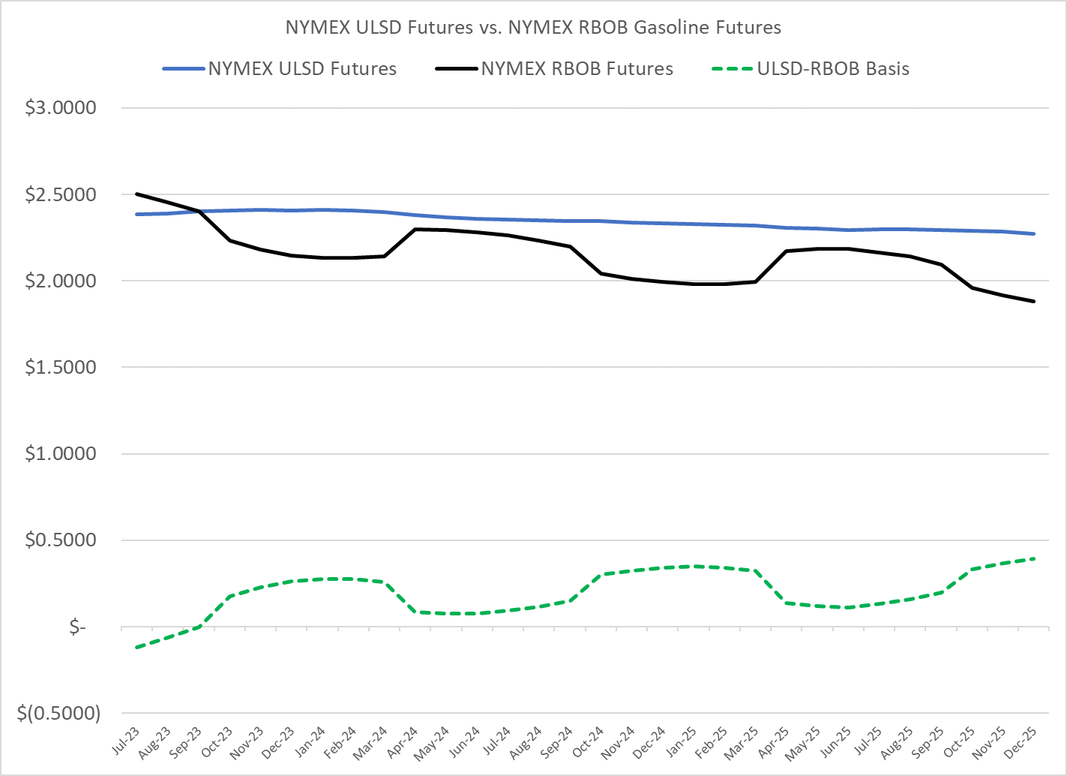

Product or quality basis risk is the risk that you encounter when you are trading or hedging with forward, future or swap which is not the same product or quality as the product that you are seeking to hedge. As an example, jet fuel is often hedged with crude oil, gasoil or ultra-low sulfur diesel fuel (and formerly, heating oil, until the contract transitioned to ultra-low sulfur diesel) as the futures, swaps and options markets for crude oil, gasoil and ULSD futures, swaps and options are much more actively traded (liquid) than the market for jet fuel futures, swaps and options. While jet fuel, gasoil and ULSD are similar (all are middle distillate fuels) and highly correlated, they are not one in the same. As a result, if one chooses to hedge jet fuel with crude oil, gasoil, ULSD or another product, they are exposing themselves to significant product or quality basis risk, and often locational basis risk as well. Many companies are of the opinion that taking on product or quality basis risk is a much better alternative to not hedging at all, an issue we will also address in a future post as well. Like the previous crude oil basis risk example, jet fuel basis risk and other product and/or quality basis risks can also be hedged via basis swaps and other strategies.

Calendar basis risk, also known as calendar spread risk, is the risk that arises from hedging with a contract that doesn't expire, settle or mature on the same date as the underlying exposure. As an example, a large consumer (i.e., a vehicle fleet) of gasoline might decide to hedge their anticipated August gasoline consumption by purchasing a September NYMEX RBOB gasoline future. In this example, the consumer is exposed to calendar basis risk as RBOB gasoline futures expire on the last day of the month prior to the delivery month i.e., the September RBOB gasoline futures contract expires on the last trading day of August while the consumer is purchasing gasoline all month, not on a single day.

While many might assume that this consumer has no choice but to accept the basis risk, this is not the case. There are other, actively traded products which will allow them to mitigate their exposure to calendar basis risk. As an example, in the OTC crude oil and refined product financial derivatives (paper) markets - including gasoline - there are futures, swaps and options that settle against the calendar month average of the prompt futures contract, an instrument which is clearly advantageous to the gasoline consumer when compared to the futures contract itself as they are consuming gasoline on a daily basis, not just the last trading day of the month.

Back to our example, if this gasoline consumer were to have hedged their August gasoline price risk with an August RBOB gasoline (calendar month average) swap, the swap would settle against the average settlement price of the prompt futures contract for each business day during August, which in this case would be the September RBOB gasoline futures contract. By utilizing the swap rather than a futures contract, the consumer has aligned their daily purchases with a hedge which is based on the calendar month average rather than a single day, which would be the case with the futures contract.

This post is a mere introduction to energy basis, basis risk and basis hedging, all of which can be rather challenging subjects to those who aren’t well versed in the subjects. As previously mentioned, we will be covering these topics in much more depth in the coming weeks and months. In the meantime, if you are interested in additional information regarding energy basis, basis risk and basis hedging, you might be interested in the following posts:

Revisiting Energy Basis Risk & The Impact on Airline Fuel Hedging

Basis Risk Leads to Unexpected Fuel Hedging Results

Energy Hedging - Back to the Basics Part IV - Basis Swaps